Ford Ranger created the compact truck market in the U.S. Ford abandoned the perennial Top Ten seller because it wouldn’t spend the money to update Ranger to make it competitive with newer Toyota and Nissan small pickups.

There’s a new book ($39.95 plus shipping and tax) published December 1 by the University of Minnesota Press, The Ford Century in Minnesota, about its Twin Cities plant.

The book will prove of considerable interest – and good reading – by and for automotive, enthusiasts, historians, journalists, as well as both Labor and Industry folks.

It’s a big book, 364 pages in a large folio format with nearly 200 photographs, many never previously published. It’s a good book that I highly recommend.

The author, Brian McMahon of Stillwater, MN is neither a “car guy,” nor an automotive historian. Rather, he’s a broader historian (trained in Architecture and Historic Preservation, thus a historian of buildings.)

Further, he’s done his homework thoroughly with research at The Henry Ford, the National Automotive History Collection at Detroit’s Public Library, in Minneapolis and St. Paul newspapers, as well as in several published Henry Ford biographies and Ford Motor Company histories, plus interviews with retired Ford employees and UAW Local officers from Ford’s Twin Cities Assembly Plant.

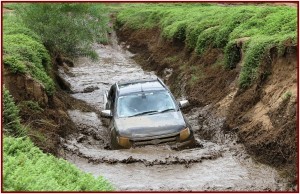

The last Ford Ranger pickup truck built in North America rolled off the assembly line on Dec. 16, 2011, at Ford’s historic Twin Cities Assembly Plant in St. Paul, Minn. More than 7 million Rangers were built since production began in 1982 at a Ford factory in Louisville, Kentucky.

McMahon’s focus is on the Twin Cities plant, home of Ranger compact truck *** production for nearly 20 years, that had a reputation among Ford executives as the highest quality Ford assembly plant in America. McMahon first covers Ford’s earlier plants to build Model T cars and tractors in Minneapolis, St. Paul and even Fargo, North Dakota, as well as their importance to Ford dealers in the Upper Midwest, and the elder Henry Ford’s fixation with “helping farmers.”

Then the fun began, as the cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, located on opposite sides of the Upper Mississippi River Valley, feuded continuously over several decades, initially over river navigation, dams in the river and a possible hydroelectric plant. The feuding became intense in the 1920s when Ol’ Henry, interested in hydroelectric power, offered to build a hydro plant and adjoining “high” dam on the St. Paul side of the river.

Later he proposed closing the two existing Minneapolis and St. Paul factories, outmoded by Ford’s moving assembly lines, to build a new plant on state park acreage at the St. Paul bluffs over the Mississippi–and then announced he would augment the approved hydro plant, with an additional conventional steam power plant, also to be on the St. Paul side. The second power plant was needed to keep the proposed Twin Cities Assembly Plant operating should the Mississippi River experience high enough flood waters to knock out the new hydro plant.

Part of the feud between the two Minnesota cities grew from perceived future division of spoils, not only employment and resulting taxable real estate development, but division of any excess electricity beyond the assembly plant’s needs. The municipalities wanted to sell it at steep discounts to their citizens. After obtaining all governmental permits, Ford solved that problem by agreeing to sell its surplus electricity to the local privately-owned electric power company, Northern States.

Then the two cities feuded over the location of a new bridge over the river between them, to accommodate plant worker traffic to and from Minneapolis. Much later, they feuded over where the new Minnesota State Fairgrounds would go, having nothing to do with the plant, St. Paul again winning. All this, the author relates in amusing detail.

Ford’s Twin Cities Assembly, opened in 1925, was designed handsomely by Detroit’s legendary Albert Kahn firm, assisted by local Twin Cities’ professionals, with residential-looking white plaster exteriors, red tile roofs, classic columns and below-level siting. Up until Ranger production ceased at the end of 2012 and the plant was shuttered and then torn down, it fitted in well – almost invisibly – with the surrounding upscale residential neighborhood developed subsequent to the plant opening.

Beginning with Model T’s, Twin Cities, along with other Ford plants across North America, assembled a variety of cars and light trucks—including US Army armored cars here for World War II—until production was initiated for Ford’s then new Ranger in 1985.

From that year, Twin Cities Assembly’s output was devoted to Ranger, along with a couple of other assembly plants. When production had to be cut back because of dwindling Ranger public demand, Twin Cities became the exclusive supplier. Later, the company decided that the more profitable, larger F-150 truck was too close to Ranger in retail transaction prices, so it decided to discontinue Ranger in the US. Subsequently Ford Asia Pacific developed a modern, very different truck with the same name for assembly outside the US; rumors from the UAW now say this different Ranger may be imported in a couple of years to the US or built at a truck plant in Wayne, Michigan.

McMahon also details various Minnesota concerns about Twin Cities Assembly, beginning with the seven-month shutdown to re-tool for Model A production in 1927, plus reduced output and employee layoffs in the Great Depression when demand for new cars was drastically reduced.

After Ford Motor Company signed a national agreement with the UAW in 1941, Local 879 was established to represent Ford’s Twin Cities workers, eventually earning a reputation as one of the UAW’s most militant locals, especially after being invaded by post-Vietnam War radicals.

If there is a flaw in the book, in this reviewer’s opinion, it may be because the author relied too much on comments by Local 879 officers and dismayed Ford workers, notably when rumors erupted of Ranger being discontinued and the plant closing with extensive layoffs of all Twin Cities employees. It seemed to me that neither the author nor his union sources understood that plants exist only to meet market demand, and not mainly to provide local societal benefits. Further, there seemed to be no understanding of the extreme cost pressures against domestic automakers from those import companies operating from protected markets.

In the end, Ford offered Twin Cities workers (and other discontinued operations either generous layoff benefits or transfers to job openings at other plants. However, few workers wanted to move from Minnesota, accepting the buy-out offers instead.

*** Ford Motor, of course, once dominated the compact pickup truck market in the U.S. until years of product neglect combined with an assault by Toyota and Nissan pushed it to a footnote in the segment. This first forced the closing of Ford’s Edison, New Jersey plant. The remaining plant in Minnesota did not survive the Ford UAW contract in 2011. It was and remains a stunning amount of business to cede to the competition. – editor

Ford dominated the compact pickup market in the U.S. until years of product neglect and an assault by Toyota and Nissan pushed it out of the segment.

AutoInformed.com on:

- Major Greed Baseball – Toyota Sponsors the Texas Rangers

- Mazda BT 50, Ford Ranger Pickup Capacity Upped in Thailand

- New Ford Ranger Debuts in Bangkok – U.S. Bound?

- Boeing Phantom Eye Uses Ford Ranger Hydrogen Engines

- Power of Ridgeline Ad takes on Other Small Pickups

- Next Mazda B-Series Pickup to be Built by Isuzu

- Ford Invests $1.6 Billion in Mexico. NAFTA Sucking Sound of Lost U.S. Jobs Continues During Fierce Presidential Race

- Honda Ridgeline Mid-Size Pickup Debuts at NAIAS

- 2016 Toyota Tacoma Pickup Debuts at NAIAS