The federal budget deficit in May was $424 billion, about double the amount in the same month last year, the Congressional Budget Office estimates. That increase stems from the economic disruption caused by the 2020 corona virus pandemic and from the federal government’s tardy response to it, followed by Congressional panic actions of four pieces of legislation: the Corona virus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, the Families First Corona virus Response Act (FFCRA), the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act (PPPHCEA). (earlier Ten-Month US Budget Deficit Now at $867 billion. $Trillion Deficits Now Certain Under Current Economic Policies)

CBO claims that in 2019, some federal payments were shifted from June to May because June 1 fell on a weekend; no such shift occurred this June. If not for those shifts in the timing of payments, the deficit in May 2020 would have been $266 billion more than the deficit last May – still a breathtaking number that some or most of it will find it’s way into our national debt that will burden future generations.

A broader view is not encouraging. After the Trump tax cuts for wealthy people and corporations, the federal budget deficit was about $1.9 trillion in the first eight months of fiscal year 2020, CBO estimates, $1.2 trillion more than the deficit recorded during the same period last year. Revenues were 11% lower and outlays were 30% higher through May of this year than during the same eight-month period in fiscal year 2019. (If not for the timing shift that benefited May, outlays would have been 32% higher.)

Receipts Down by 25% in May

CBO estimates that receipts in May totaled $175 billion—$58 billion (or 25%) less than those in May 2019. Receipts fell for several reasons: declines in wages and in economic activity generally, recently enacted legislation, and actions by the Administration.

Estimated changes in May relative to last year:

- Individual income and payroll (social insurance) taxes together decreased by $51 billion (or 24%). Most of that decline is attributable to a decrease in the amounts withheld from workers’ paychecks.

- Amounts withheld fell by $31 billion (or 15%) because of a decline in wages and because of recently enacted legislation. The CARES Act allows most employers to defer payment of their portion of the Social Security payroll tax and certain Railroad Retirement taxes on wages paid from March 27, 2020, through December 31, 2020. In addition, FFCRA provides refundable credits against payroll taxes to compensate employers for paid sick leave and for family and medical leave, and the CARES Act provides a refundable credit against payroll taxes for employee retention.

- Individual income tax refunds increased by $21 billion (or 140%), further reducing net individual income tax receipts. That increase probably reflects refunds that would have been paid in April if the Administration had not delayed the tax-filing deadline until July 15, 2020.

- Corporate income taxes fell by $2 billion, reflecting a decline of $4 billion (or 60%) in corporate income tax payments, partially offset by a decrease of $2 billion (or 34%) in corporate refunds. CBO anticipates an increase in corporate tax refunds over the remainder of the year, resulting from the CARES Act’s temporary modifications to the treatment of net operating losses.

- Receipts from other sources decreased by $4 billion (or 21%), primarily driven by excise taxes, which decreased by $5 billion (or 60%).

Higher Spending in May Responding to the Pandemic

Total spending in May 2020 was $598 billion, CBO estimates—36% higher than the sum in May 2019. If not for the shift of some federal payments from June 2019 to May 2019, total spending would have been 53% higher in May 2020 than in the same month last year.

May 2020 was the first month that saw significant budgetary effects from PPPHCEA (enacted on April 24). In addition, spending stemming from earlier legislation, most notably the CARES Act (enacted on March 27), continued in May.

Major changes in outlays in May that were related to the pandemic were as follows (the amounts reflect adjustments to exclude the effects of the timing shifts)

- Outlays for unemployment compensation increased from $2 billion in May 2019 to $93 billion this year. More than half of that rise stems from a $600 increase in the weekly benefit amount provided under the CARES Act. Benefits for regular unemployment compensation rose as well.

- Payments for refundable tax credits were $53 billion (compared with $3 billion in May 2019). That difference is attributable primarily to the CARES Act’s recovery rebates, which began to be paid in April and continued in May.

- Outlays by the Small Business Administration increased from $98 million to $35 billion, primarily because of loans and loan guarantees to small businesses through the Paycheck Protection Program authorized by the CARES Act and PPPHCEA. (CBO estimates that payments for the program will total $670 billion during this fiscal year.)

- Outlays for the Public Health Social Services Emergency Fund totaled $27 billion this May, compared with $250 million last May. Funding was increased by recent legislation to reimburse health care providers (such as hospitals) for health care costs or lost revenues resulting from the pandemic. The remaining amounts are available to develop countermeasures, vaccines, and technologies and to develop, purchase, administer, process, and analyze tests for COVID-19, the disease caused by the corona virus.

- Outlays for the Corona virus Relief Fund, authorized by the CARES Act to provide grants to state, local, tribal, and territorial governments to offset pandemic-related expenses, totaled $5 billion in May. There was no such spending last year.

- Spending by the Department of the Treasury for aviation worker relief totaled $5 billion in May. The CARES Act authorized that assistance for payroll support in the form of grants and loans.

- Outlays from the Department of the Treasury’s Exchange Stabilization Fund increased from –$47 million to $4 billion, almost entirely because of equity investments in certain Federal Reserve facilities, which provide liquidity for a wide range of economic activities. Those facilities are designed to address financial strain caused by the pandemic. CBO expects that the increase in the deficit caused by those outlays will probably be offset in future years by payments to the Treasury from the facilities’ proceeds.

- Medicare outlays were $6 billion (or 9%) lower because the use of health care by Medicare beneficiaries has declined for care that is not associated with the corona virus.

First Eight Months Deficit More Than Doubled

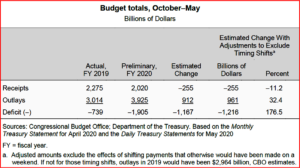

The federal budget deficit was $1,905 billion in the first eight months of fiscal year 2020, CBO estimates, $1,167 billion more than the deficit recorded during the same period last year. Revenues were lower and outlays were higher than during the same period in fiscal year 2019.

- Shifts in the timing of certain payments increased outlays in the first eight months of last year by $49 billion. If not for those shifts last year, the increase in the deficit so far, this fiscal year would have been $1,216 billion.

- Total Receipts: Down by 11% in the First Eight Months of Fiscal Year 2020

- Receipts totaled $2,020 billion during the first eight months of fiscal year 2020, CBO estimates—$255 billion less than during the same period last year. Through March, receipts were running 6% above last year’s amounts; in April, receipts declined sharply; and through May, they were 11% below last year’s amounts.

- Revenue collections in fiscal year 2020 can be divided into two periods: before and after the start of the economic disruption caused by the pandemic.

- Revenues in the first six months of the fiscal year—October 2019 through March of 2020—were 6% higher than in the previous fiscal year. The increase in revenues stemmed primarily from the following:

- Individual income and payroll (social insurance) taxes, which largely reflect increases in wages and salaries.

- Corporate income taxes, mostly from quarterly estimated payments for tax year 2019.

- Receipts from other sources, notably increases in Federal Reserve remittances and customs duties, which were partly offset by a decline in excise taxes.

Revenues collected after the economic disruption began, notably collections in April and May, fell by 46% compared with the same period last year, largely because of declines in wages and in other economic activity, recently enacted legislation, and administrative actions. Among the most significant of those actions was the Administration’s delay of individual and corporate tax-filing and payment deadlines from April 15 until July 15.

CBO expects that much of the deferred revenue, including that resulting from administrative actions as well as recently enacted legislation, will be collected later this year; some is expected to be collected in future fiscal years.

However, because some individual taxpayers or businesses could become insolvent and fail to remit the future payments, the government might not collect all those deferred amounts.

Other changes, including changes attributable to the sharp decline in economic activity and to legislation (such as the deferral of and credits for certain payroll taxes), further reduced receipts beginning in April and will continue to do so through the rest of the fiscal year.

Major changes in revenues in April and May 2020, compared with the same two months in 2019, are linked to the pandemic and the government’s response to it:

- Individual income and payroll (social insurance) taxes together decreased by $305 billion (or 45%).

- Nonwithheld payments of income and payroll taxes fell by $281 billion (or 87%). That decline was largely a result of the delay in the tax-filing deadline.

- Individual income tax refunds decreased by $38 billion (or 48%). That decline also is probably the result of the later tax-filing deadline.

- Amounts withheld from workers’ paychecks decreased by $61 billion (or 15%) because of a decline in wages and recently enacted legislation, as discussed above.

- Corporate income taxes fell by $43 billion (or 94%), largely because of the delay in the tax-filing deadline for corporations.

- Receipts from other sources increased by $4 billion (or 9%). That increase was primarily the net result of offsetting changes in the following sources:

- Federal Reserve remittances increased by $8 billion (or 77%), in part because of lower short-term interest rates, which reduce the Federal Reserve’s interest expenses and therefore increase its remittances to the Treasury. As part of its efforts to carry out monetary policy in response to the pandemic, the Federal Reserve also has significantly increased its holdings of assets, which tends to further increase remittances.

- Excise taxes fell by $11 billion (or 77%), in part because the CARES Act suspended the collection of certain aviation excise taxes for the rest of the calendar year. The Administration also delayed due dates for other excise taxes, including those on wine, beer, distilled spirits, tobacco products, firearms, and ammunition. The general reduction in economic activity also contributed to the decline.

- Estate and gift tax collections decreased by $3 billion (or 88%).

Outlays Up by 30% First Eight Months of FY 2020

Outlays for the first eight months of fiscal year 2020 were $3,925 billion, $912 billion higher than they were during the same period last year, CBO estimates. If not for the shift in the timing of certain payments last year, that year-to-year increase would be larger—$961 billion, or 32%.

Outlays in fiscal year 2020 can be divided into spending before the government’s pandemic response (October 2019 through March 2020) and after the response began (April and May 2020).

October Through March. From October through March, outlays were $2,347 billion—$149 billion (or 7%) higher than they were during the same period last year. The increase stemmed primarily from the following:

- Social Security (more beneficiaries and higher average benefits).

- Medicare (more beneficiaries and higher health costs per capita).

- Medicaid (higher health costs per capita).

- Department of Defense (increases for procurement and for operations and maintenance).

- Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (the Treasury received $11 billion less in payments from those two entities).

- Net interest on the public debt (primarily because the debt has grown).

- Department of Veterans Affairs (the number of people receiving disability compensation rose, average disability benefits increased, and spending rose for a program that allows veterans to receive treatment in facilities other than those operated by the department).

April and May: Outlays in April and May 2020 were nearly twice what they were in the same two months last year—increasing by $763 billion. Large increases are linked to the pandemic and the federal government’s response to it:

- Payments of refundable tax credits—including the CARES Act’s recovery rebates, which started in April—have totaled $275 billion.

- Outlays totaling $147 billion were made from the new Coronavirus Relief Fund in April and May.

- Outlays for unemployment compensation were $136 billion more in April and May than in the same two months in 2019 because of the increase in unemployment benefits provided by the CARES Act along with the increase in regular unemployment benefits.

- Outlays for the Public Health Social Services Emergency Fund were $57 billion, compared with $500 million for the same two-month period last year.

- Outlays by the Small Business Administration were $50 billion in April and May of 2020, compared with less than $200 million during those two months last year.

- Spending by the Department of the Treasury for aviation worker relief totaled $18 billion in April and May.

- Spending on Medicaid was $15 billion higher in April and May than in the same period last year for three reasons: increased enrollment; the 6.2%age-point increase in federal matching rates that states began to access in April 2020 (enacted in FFCRA); and FFCRA’s requirement that states maintain enrollees on Medicaid until the end of the public health emergency.

- Outlays from the Department of the Treasury’s Exchange Stabilization Fund were $14 billion in April and May, compared with -$100 million in those months last year.

Actual is a $738 Billion Deficit in April 2020

The Treasury Department reported a deficit of $738 billion for April—$1 billion higher than CBO estimated last month, on the basis of the Daily Treasury Statements, in the Monthly Budget Review for April 2020.

The federal government uses several accounting mechanisms to link earmarked receipts (that is, money designated for a specific purpose) with corresponding expenditures. One of those mechanisms is trust funds. When the receipts designated for trust funds exceed the amounts needed for expenditures, the funds are credited with non-marketable debt instruments known as Government Account Series (GAS) securities, which are issued by the Treasury. At the end of fiscal year 2019, trust funds held $5.2 trillion in such securities.

The federal budget has numerous trust funds, although most of the money credited to them goes to fewer than a dozen. By far the largest trust funds are Social Security’s Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund and the funds dedicated to the government’s retirement programs for its military and civilian personnel (Social security is now threatened by President Trump. Feeling safe under his reign? – editor.)

According to the Congressional Budget Office’s current baseline budget projections, the balances held by federal trust funds will fall by $43 billion in fiscal year 2020. That amount is $100 billion lower than the $57 billion surplus that the agency estimated in January, when it last published its baseline budget projections for the major trust funds. The change in CBO’s estimate was largely driven by an increase in payments made by the Unemployment Trust Fund as the number of beneficiaries increased.

Spending from the trust funds is projected to exceed income by $18 billion in 2021, a deficit that grows to $502 billion by 2030. Over the 2021–2030 period, CBO projects a cumulative trust fund deficit of $2.3 trillion, on net. That amount is $130 billion (or 6%) larger than the $2.2 trillion deficit that the agency estimated in January 2020. The projections for deficits were revised upward in part because of the economic disruption stemming from the 2020 corona-virus pandemic, which reduced CBO’s estimates of payroll tax revenues. (The ongoing lack of a Trump Administration plan to attack Covid-19 has severely hurt the economy and needlessly killed people in the US. – editor)

If the Congress does not take action to address the shortfalls, CBO projects, the balances in three trust funds would be exhausted within the next 10 years: the Highway Trust Fund (in fiscal year 2021), Medicare’s Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund (in fiscal year 2024), and Social Security’s Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund (in fiscal year 2026). No provisions in law dictate the funds’ procedures once their balances are depleted. However, if that happened, excise and payroll taxes designated for the funds would continue to be collected, and the funds would continue to make payments, but they would not have the authority to make payments in excess of receipts. Thus they would no longer be able to pay amounts as projected under current law.