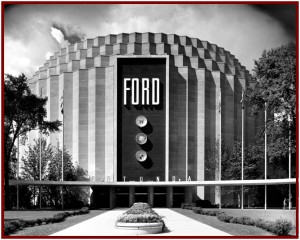

The city of Detroit Common Council and Mayor Dave Bing are currently debating plans to raze the 55-year-old landmark Ford Auditorium on Jefferson Avenue at the foot of Woodward Avenue in downtown Detroit.

Ford Auditorium has been unused and empty for years despite its prime riverfront site.

The mayor wants to tear it down so the property can be used—hopefully sold to respectable developers—and, though unsaid, it therefore would become taxable.

Detroit, like most municipalities and other government jurisdictions, is hurting for tax revenue that doesn’t impact the citizenry, who are near rebellion in many places across the country.

The Common Council is digging in its heels, with some members saying, probably wisely, that they don’t want to approve the demolition until they see who the buyer will be and just how the property will be used.

Still, it must be causing anguish among the Ford family, now headed by octogenarian Detroit Lions owner William Clay Ford, his son Ford Motor Company chairman Bill Jr., and nephew Edsel Ford II, also a director of the company.

When the Ford Auditorium opened, 1956 was a big year for the Ford family and the company. Family matriarch Eleanor Clay Ford, widow of Henry One’s only son Edsel, and a significant civic leader, had pledged many millions of her personal fortune to build the Auditorium so that it would be the new star of downtown Detroit, replacing aging warehouses along the Detroit Riverfront.

In parallel it also was a big year for the Ford Motor Company. Ford car sales in 1955 were narrowly eclipsed by Chevrolet due in part to some last minute registration shenanigans, but Ford was to go on to take the Number One sales flag for 1957, the first time since 1935.

Moreover, the Ford Foundation created with the gift of Ford family stock in 1936, “went public” in 1956 and distributed thousands of shares of Ford stock. For the first time ordinary people as well as investment houses could own and trade Ford Motor Company common stock, new public partners with the family.

So the Ford Auditorium was Detroit’s and the Ford family’s shining new showplace when I arrived here in 1957 from the Miami Daily News to be assistant manager of the Business Week bureau. Ford Auditorium was home of the Detroit Symphony and venue for all sorts of performance and civic events. Detroit was at its peak of population and prosperity.

It was here that Bob Hefty, at the time Ford’s press relations manager, introduced me to then vice president Richard Nixon when Nixon was about to run for President (I never knew what Bob’s connection to Nixon was, and in my many years of later working for Bob at Ford, never asked.)

Nixon was about to give a speech to the Detroit Seven Sisters organization, made up of area alumna of the seven elite women’s colleges in New England. Bob saw me in the lobby with my wife (a Seven Sister) and asked if we’d like to meet the Vice President. He led us backstage for the introduction. Even offstage there was a huge, noisy crowd, so I asked Nixon something to the effect of What Do You Do If You Have Claustrophobia? His response, “I guess you don’t go into politics.” It was one of my moments in history and nailed down my memory of Ford Auditorium.

But from the day of its opening, the killing problem with the Auditorium was its total acoustical engineering failure: performances of the Symphony or any like performance were awful. Not only the patrons in the audience could not hear clearly, neither could the musicians on stage. The Fords dumped a ton of money into acoustical re-engineering trying to fix the problem but ultimately had to give up.

The whole Detroit community was shamed, the once star-quality structure becoming a nagging white elephant, indeed right in the morning shadow of Henry Ford II’s towering Renaissance Center (now the headquarters of General Motors a block to the northeast.) In an irony of history the RenCen has been observed by some to constitute another avant garde architectural monstrosity.

The musical fix was many years coming. That happened when the 1920s Orchestra Hall a mile or so north on Woodward Avenue was completely refurbished and the Symphony moved back in there in 1989, returning to its original home.

Unfortunately–and symptomatic of Detroit problems–for the last several months there has been no Detroit Symphony season because of an impasse in labor negotiations between the musicians and Symphony management.

Aside from Nixon, one of the most famous speeches at Ford Auditorium was one delivered by Malcolm X in 1965, reportedly his last public address outside New York City before his death.

Barring a miracle the Ford Auditorium, like two other famous Ford Buildings in Dearborn – the Rotunda, which burned and was not rebuilt, and the old Executive Office building, with its stunning Art Deco design, which fell to a wrecking ball – will vanish from the landscape.