A sharp drop in the rate of growth of manufacturing output between 2000 and 2007 was responsible for the huge decline in manufacturing employment.

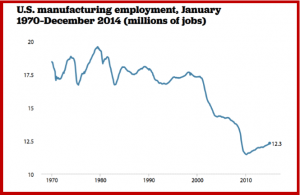

After holding relatively steady for 30 years, U.S. manufacturing employment began declining rapidly in 2000, falling to a low of 11.5 million in February 2010. This manufacturing job loss can be traced to growing trade deficits throughout the decade, and the collapse of manufacturing output following the Great Recession. It was not rapid gains in productivity from technological advancements that caused the employment crisis, according to Manufacturing Job Loss, a new issue brief from EPI Director of Trade and Manufacturing Research Robert E. Scott.

“Manufacturing job losses are not the inevitable result of technological progress. They were caused by trade policy, and they can be reversed by trade policy. We are not losing manufacturing jobs to robots, we’re losing them to China,” said Scott.

“Our job losses are the result of failed currency and macroeconomic policies. They can be reversed by aggressive enforcement of fair trade laws, taking action to end currency manipulation, and through major commitments to rebuilding America’s crumbling infrastructure, starting with long-term renewal of the transportation funding bill that is currently being held up in the House of Representatives.”

Contrary to popular belief, as manufacturing employment began its decline around 2000, manufacturing productivity growth slowed as well. The reason for this slowdown was the U.S. manufacturing trade deficit, which began to rise sharply. Overall, manufacturing output growth fell drastically between 2000 and 2007, compared to the previous decade, as imports reduced demand for U.S. goods.

Between 2007 and 2014, meanwhile, productivity growth declined even further, and manufacturing output stagnated because of the Great Recession. The manufacturing recovery has also been slowed by growth of the manufacturing trade deficit since 2009. Manufacturing employment hit a low of 11.5 million in 2010, before recovering slightly to 12.3 million in 2014.