Click to Enlarge.

Optimism by European automakers and analysts, with now wrongful claims that vehicle output would improve markedly in the second half of 2021 are a stark lesson in the resilience of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

The most recent setback has been the forced closure of semiconductor facilities in Malaysia to contain the latest COVID-19 outbreak, the LMC Automotive consultancy notes. This disaster comes from raw material price increases, semiconductor shortages and bottlenecks in the production of intermediate products.

“Undeniably, the major constraint to European Light Vehicle output so far this year has been the scarcity of chips, which is estimated to account for roughly 80% of the total loss in output from our pre-crisis expectations,” said LMC. “Meanwhile, shortages of other vehicle components, such as wiring harnesses and brake parts, have further exacerbated the slowdown, albeit to a lesser extent.”

The usual economic principles no longer apply, or they are upside down. Through to the end of Q3 this year, LMC estimates that almost 1.5 million fewer vehicles were produced in Europe because of chip supply disruptions. “These losses are substantial, so much so that vehicle inventories are running too low to adequately supply buoyant demand for new cars,” said LMC.

This is a significant shift. Vehicle inventories are running too low to supply upbeat demand for new cars. The inverse economic law is usually true: with demand dictating the level of supply. The crisis has increasingly steered market power away from consumers. Indeed Toyota announced today that it will suspend production for several days in Japan during October at 27 lines in 14 plants out of 28 lines in 14 plants.

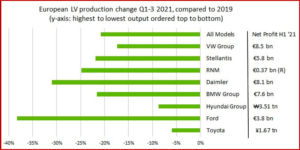

Nonetheless automakers have improved profitability during the first half of 2021 (see chart above for H1 CY net profit figures) by give precedence to high-margin models and raising vehicle prices to offset higher input costs. Moreover, manufacturers have continued the cost-reduction work started pre-pandemic, including capacity and model line-up rationalizations.

Unfortunately, supply constraints and inflationary pressures will certainly persist until the chip shortage is resolved. This miracle will require greater chip allocation to the automotive industry. But the cost and complex nature of semiconductor manufacturing means that it takes years for production capacity to expand.

“We therefore expect disruptions to European Light Vehicle production to continue until at least 2023, at which point output volumes are set to just about recover to 2019 (pre-pandemic) levels,” said LMC.

About Ken Zino

Ken Zino, editor and publisher of AutoInformed, is a versatile auto industry participant with global experience spanning decades in print and broadcast journalism, as well as social media. He has automobile testing, marketing, public relations and communications experience. He is past president of The International Motor Press Assn, the Detroit Press Club, founding member and first President of the Automotive Press Assn. He is a member of APA, IMPA and the Midwest Automotive Press Assn.

He also brings an historical perspective while citing their contemporary relevance of the work of legendary auto writers such as Ken Purdy, Jim Dunne or Jerry Flint, or writers such as Red Smith, Mark Twain, Thomas Jefferson – all to bring perspective to a chaotic automotive universe.

Above all, decades after he first drove a car, Zino still revels in the sound of the exhaust as the throttle is blipped during a downshift and the driver’s rush that occurs when the entry, apex and exit points of a turn are smoothly and swiftly crossed. It’s the beginning of a perfect lap.

AutoInformed has an editorial philosophy that loves transportation machines of all kinds while promoting critical thinking about the future use of cars and trucks.

Zino builds AutoInformed from his background in automotive journalism starting at Hearst Publishing in New York City on Motor and MotorTech Magazines and car testing where he reviewed hundreds of vehicles in his decade-long stint as the Detroit Bureau Chief of Road & Track magazine. Zino has also worked in Europe, and Asia – now the largest automotive market in the world with China at its center.

European Light Vehicle Production Tanking

Click to Enlarge.

Optimism by European automakers and analysts, with now wrongful claims that vehicle output would improve markedly in the second half of 2021 are a stark lesson in the resilience of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

The most recent setback has been the forced closure of semiconductor facilities in Malaysia to contain the latest COVID-19 outbreak, the LMC Automotive consultancy notes. This disaster comes from raw material price increases, semiconductor shortages and bottlenecks in the production of intermediate products.

“Undeniably, the major constraint to European Light Vehicle output so far this year has been the scarcity of chips, which is estimated to account for roughly 80% of the total loss in output from our pre-crisis expectations,” said LMC. “Meanwhile, shortages of other vehicle components, such as wiring harnesses and brake parts, have further exacerbated the slowdown, albeit to a lesser extent.”

The usual economic principles no longer apply, or they are upside down. Through to the end of Q3 this year, LMC estimates that almost 1.5 million fewer vehicles were produced in Europe because of chip supply disruptions. “These losses are substantial, so much so that vehicle inventories are running too low to adequately supply buoyant demand for new cars,” said LMC.

This is a significant shift. Vehicle inventories are running too low to supply upbeat demand for new cars. The inverse economic law is usually true: with demand dictating the level of supply. The crisis has increasingly steered market power away from consumers. Indeed Toyota announced today that it will suspend production for several days in Japan during October at 27 lines in 14 plants out of 28 lines in 14 plants.

Nonetheless automakers have improved profitability during the first half of 2021 (see chart above for H1 CY net profit figures) by give precedence to high-margin models and raising vehicle prices to offset higher input costs. Moreover, manufacturers have continued the cost-reduction work started pre-pandemic, including capacity and model line-up rationalizations.

Unfortunately, supply constraints and inflationary pressures will certainly persist until the chip shortage is resolved. This miracle will require greater chip allocation to the automotive industry. But the cost and complex nature of semiconductor manufacturing means that it takes years for production capacity to expand.

“We therefore expect disruptions to European Light Vehicle production to continue until at least 2023, at which point output volumes are set to just about recover to 2019 (pre-pandemic) levels,” said LMC.

About Ken Zino

Ken Zino, editor and publisher of AutoInformed, is a versatile auto industry participant with global experience spanning decades in print and broadcast journalism, as well as social media. He has automobile testing, marketing, public relations and communications experience. He is past president of The International Motor Press Assn, the Detroit Press Club, founding member and first President of the Automotive Press Assn. He is a member of APA, IMPA and the Midwest Automotive Press Assn. He also brings an historical perspective while citing their contemporary relevance of the work of legendary auto writers such as Ken Purdy, Jim Dunne or Jerry Flint, or writers such as Red Smith, Mark Twain, Thomas Jefferson – all to bring perspective to a chaotic automotive universe. Above all, decades after he first drove a car, Zino still revels in the sound of the exhaust as the throttle is blipped during a downshift and the driver’s rush that occurs when the entry, apex and exit points of a turn are smoothly and swiftly crossed. It’s the beginning of a perfect lap. AutoInformed has an editorial philosophy that loves transportation machines of all kinds while promoting critical thinking about the future use of cars and trucks. Zino builds AutoInformed from his background in automotive journalism starting at Hearst Publishing in New York City on Motor and MotorTech Magazines and car testing where he reviewed hundreds of vehicles in his decade-long stint as the Detroit Bureau Chief of Road & Track magazine. Zino has also worked in Europe, and Asia – now the largest automotive market in the world with China at its center.