The fourth round of North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) negotiations between the United States, Canada, and Mexico began October 11, 2017 in Washington, D.C.

“So far, the previous rounds of negotiations have produced little progress on the issues of greatest concern to the automotive industry, and this slow pace of resolving issues on the table calls into question the prospect of wrapping up negotiations by the end of the calendar year, according to the respected think tank The Center for Automotive Research, aka CAR.

Rules of Origin

Rules of Origin (ROO) are one of the hardest NAFTA issues for the automotive industry, in CAR’s view. Currently, NAFTA contains a 62.5% threshold for Regional Value Content (RVC) in motor vehicles and parts, which is the highest ROO of any U.S. trade agreement.

The Trump Administration has recently proposed:

- Raising the NAFTA RVC to 85%,

- Requiring 50% U.S. content as part of the 85% RVC,

- Including all parts, components, and materials in a light vehicle to “modernize” the tracing list, and finally,

- Instituting a validation process for content, rather than the current process whereby manufacturers can “deem originating” for parts, components, and vehicles produced within the NAFTA region.

“The intent of tracing is to prevent manufacturers from ‘rolling up imported content that originates from outside North America, said CAR. “In other words, an engine assembled in one of the three NAFTA partner countries that contains non-NAFTA parts or components would not be considered 100% NAFTA originating; the non-NAFTA value must be subtracted from the total value. Currently, only items on the tracing list must be accounted for, and everything not on the list is deemed originating.”

This means that the inclusion of materials and all motor vehicle parts and components would change the rules of the game. Now there are differences in RVC levels between cars (that often have lower NAFTA content due to global platforms and global supply chains) and CUVs/SUVs/trucks (that often have higher NAFTA content due to regional production and supply chains).

Auto manufacturers could decide that the higher RVC threshold and the proposed validation process is too costly, and that it would be less costly to eschew the NAFTA preference for the 2.5% Most Favored Nation (MFN) tariff on motor vehicles and parts imported to the United States.

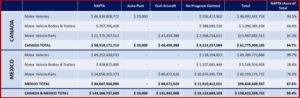

Importing vehicles, parts, and components under MFN tariffs opens the supply chain to countries beyond NAFTA, and could result in lower overall NAFTA content in vehicles produced in Canada, Mexico, and the United States. In 2016, 94.7% of U.S. imports from Canada were traded using the NAFTA preference, and 87.6% of motor vehicles, bodies & trailers, and parts from Mexico utilized the NAFTA preference.

A Poison Pill

While the Canadian and Mexican negotiating teams have many points of disagreement with the Trump Administration’s NAFTA bargaining positions, the U.S. proposal to include a “sunset clause” in the new agreement has drawn perhaps the sharpest rebukes from the trading partners, as well as from U.S. business groups including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. The Administration has proposed a provision that would force NAFTA renegotiation every five years—a move that would inject additional risk into any long-term manufacturing investment, production footprint, and supply chain sourcing decisions.

Timing

From the beginning, all three NAFTA countries have expressed the intent to expedite the NAFTA renegotiations to get out in front of next year’s Presidential elections in Mexico, Ontario Provincial elections in Canada, and the Congressional mid-term elections in the United States.

While “fast track” authority under the Trade Preferences Extension Act of 2015 technically expires July 1, 2021, there is a provision in the law that allows the U.S. Congress the opportunity to cancel the next three years of fast track authority prior to July 1, 2018. This means that the Congress could revoke fast track authority by next July, and this possibility puts additional pressure on negotiators to reach a deal on a revised NAFTA before next summer.

The Trump Administration’s move to place a 300% tariff on Canadian-built Bombardier aircraft in a trade dispute with Boeing could also alter the timeframe for negotiations. The United States claims that the aircraft are built with unfair subsidies from the Canadian government, and the U.S. action involves other countries since major parts of the airplane in question are built in Northern Ireland. The proposed duties do not go into effect unless affirmed by the U.S. International Trade Commission in early 2018. The aircraft dispute will hang over the NAFTA negotiations, and could impede the ability to reach an agreement on other aspects of trade between the United States and Canada.

What If Negotiators Do Not Reach an Agreement by The End of 2018?

There are three main options if the NAFTA negotiators do not reach a new agreement: the parties could continue to negotiate, knowing that there would be limited time to get the agreement approved in all three countries; the three countries could agree to continue trading under the existing agreement; or one or more parties could withdraw from NAFTA, effectively terminating the agreement.

The last option—terminating the agreement—is a very real possibility. The U.S. Congressional Research Service has written several reports that detail what could happen if NAFTA was terminated, and there are no clear-cut answers (Canis, Villarreal, & Jones, 2017), (Villarreal & Fergusson, The North American Free Trade Agreement, 2017), (Villarreal, U.S.-Mexico Economic Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications, 2017), (CRS Reports & Analysis: Legal Sidebar, 2017). Trade dispute resolution mechanisms would disappear; the U.S. and Canada would have to decide whether to reinstate their previous bi-lateral trade agreement; and Congress would have to rescind NAFTA’s enabling legislation, and that could be a tall order.

However, the most likely outcome, according to the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), is that the parties will “muddle through” with concessions on specific products and some “modernization.” PIIE researchers project that renegotiation will stretch beyond December 2017. What exactly those concessions will be, or what form “modernization” might take will be better known, but certainly not concluded from this round of negotiations. In short, no one “wins.” (Hufbauer, Jung, & Kolb, 2017).