Sooner or later, Nit Twit Trump is going to have to come clean about his blatant Healthcare lying over replacing the Affordable Healthcare Act with something better. I guess “better ” in Trump-speak means massive tax cuts for the rich that demonstrably will hurt the less wealthy. This isn’t healthcare – it’s highway robbery from the “liar in chief. ”

Sooner or later, Nit Twit Trump is going to have to come clean about his blatant Healthcare lying over replacing the Affordable Healthcare Act with something better. I guess “better ” in Trump-speak means massive tax cuts for the rich that demonstrably will hurt the less wealthy. This isn’t healthcare – it’s highway robbery from the “liar in chief. ”

Look at an analysis by the independent and widely respected Congressional Budget Office that was released this week, and promptly dismissed by Republicans as bogus. In the analysis, the highly respected, independent CBO says that 24 million people – mostly poor – will lose health service while giant, unimaginable tax cuts will go to the super rich.

The Concurrent Resolution on the Budget for Fiscal Year 2017 directed the Right Wing Republican-dominated House Committees on Ways and Means, and Energy and Commerce to develop legislation to reduce the deficit. (by giving tax cuts to the rich and screwing the blue collar people who voted for him?), which they don’t talk about much except in dubious, prevaricating sound bites.

The Congressional Budget Office and the staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) have an estimate of the budgetary effects of Trumps (anti-)American Health Care Act, which combines the pieces of legislation approved by the two committees to support that resolution. In consultation with the budget committees, CBO used a March 2016 baseline with adjustments for subsequently enacted legislation, which underlies the resolution, as the benchmark to measure the cost of the legislation.

Effects on the Federal Budget

CBO and JCT estimate that enacting the legislation would reduce federal deficits by $337 billion over the 2017-2026 period.

That total consists of $323 billion in on-budget savings and $13 billion in off-budget savings.

Outlays would be reduced by $1.2 trillion over the period, and revenues would be reduced by $0.9 trillion. This seems a trivial trade off for the trouble it would cause our less fortunate citizens by breaking their backs to fatten the already fat wallets of the the super-rich.

- The largest savings would come from reductions in outlays for Medicaid and from the elimination of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) subsidies for non-group health insurance. Small businesses, including those in the auto industry will get hurt here.

- The largest costs would come from repealing many of the changes the ACA made to the Internal Revenue Code—including an increase in the Hospital Insurance payroll tax rate for high-income taxpayers, a surtax on those taxpayers’ net investment income, and annual fees imposed on health insurers—and from the establishment of a new tax credit for health insurance.

Effects on Health Insurance Coverage

CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation projected how the legislation would change the number of people who obtain federally subsidized health insurance through Medicaid, the non-group market, and the employment-based market, as well as many other factors.

They estimate that, in 2018, 14 million more people would be uninsured under the legislation than under current law. Most of that increase would stem from repealing the penalties associated with the individual mandate. Some of those people would choose not to have insurance because they chose to be covered by insurance under current law only to avoid paying the penalties, and some people would forgo insurance in response to higher premiums. The whole idea of insurance is to have the largest pool possible to spread the risks and costs.

Later, following additional changes to subsidies for insurance purchase klonopin online purchased in the non-group market and to the Medicaid program, the increase in the number of uninsured people relative to the number under current law would rise to 21 million in 2020, then to 24 million in 2026. The reductions in insurance coverage between 2018 and 2026 would in large part from changes in Medicaid enrollment—because some states would discontinue their expansion of eligibility, some states that would have expanded eligibility in the future would choose not to do so, and per-enrollee spending in the program would be capped. In 2026, an estimated 52 million people would be uninsured, compared with 28 million who would lack insurance that year under current law.

Health Insurance Market Stability

Decisions about offering and purchasing health insurance depend on the stability of the health insurance market—that is, on having insurers participating in most areas of the country and on the likelihood of premiums not rising in an unsustainable spiral. The market for insurance purchased individually (that is, non-group coverage) would be unstable, if the people who wanted to buy coverage at any offered price would have average health care expenditures so high that offering the insurance would be unprofitable. In CBO and JCT’s assessment, however, the non-group market would probably be stable in most areas under either current law or the legislation. This is a big wager with unknown odds.

Under current law, most subsidized enrollees purchasing health insurance coverage in the non-group market (self employed and small businesses) are largely insulated from increases in premiums because their out-of-pocket payments for premiums are based on a percentage of their income; the government pays the difference. The subsidies to purchase coverage combined with the penalties paid by uninsured people stemming from the individual mandate are anticipated to cause sufficient demand for insurance by people with low health care expenditures for the market to be stable.

Under the legislation, in the agencies’ view, factors bringing about market stability include subsidies to purchase insurance, which would maintain sufficient demand for insurance by people with low health care expenditures, and grants to states from the Patient and State Stability Fund, which would reduce the costs to insurers of people with high health care expenditures.

Even though the new tax credits would be structured differently from the current subsidies and would generally be less generous for those receiving subsidies under current law, the other changes would, in the agencies’ view, lower average premiums enough to attract enough relatively healthy people to stabilize the market. This key assumption is a big bet.

Effects on Premiums

The legislation would tend to increase average premiums in the non-group market prior to 2020 and lower average premiums thereafter, relative to projections under current law. In 2018 and 2019, per CBO and JCT’s estimates, average premiums for single policyholders in the non-group market would be 15% to 20% higher than under current law, mainly because the individual mandate penalties would be eliminated, inducing fewer comparatively healthy people to sign up.

Starting in 2020, the increase in average premiums from repealing the individual mandate penalties would be more than offset by the combination of several factors that would decrease those premiums: grants to states from the Patient and State Stability Fund (which CBO and JCT expect to largely be used by states to limit the costs to insurers of enrollees with very high claims); the elimination of the requirement for insurers to offer plans covering certain percentages of the cost of covered benefits; and a younger mix of enrollees. By 2026, average premiums for single policyholders in the non-group market under the legislation would be roughly 10% lower than under current law, CBO and JCT estimate.

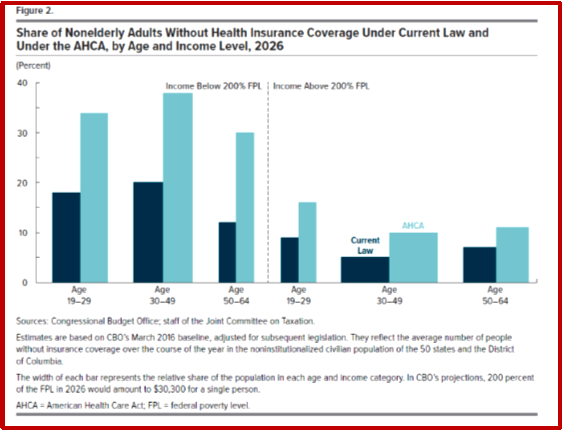

Although average premiums would increase prior to 2020 and decrease starting in 2020, CBO and JCT estimate that changes in premiums relative to those under current law would differ significantly for people of different ages because of a change in age-rating rules. Under the legislation, insurers would be allowed to generally charge five times more for older enrollees than younger ones rather than three times more as under current law, substantially reducing premiums for young adults and substantially raising premiums for older people.

Uncertainty Surrounding the Estimates

The ways in which federal agencies, states, insurers, employers, individuals, doctors, hospitals, and other affected parties would respond to the changes made by the legislation are all difficult to predict, so the estimates in this report are uncertain. But CBO and JCT have developed estimates that are in the middle of potential outcomes.

Macroeconomic Effects

Because of the magnitude of its budgetary effects, this legislation is “major legislation,” as defined in the rules of the House of Representatives. Hence, it triggers the requirement that the cost estimate, to the greatest extent practicable, include the budgetary impact of its macroeconomic effects. However, because of the very short time available to prepare this cost estimate, quantifying and incorporating those macroeconomic effects have not been practicable.

Intergovernmental and Private-Sector Mandates

JCT and CBO have reviewed the provisions of the legislation and determined that they would impose no intergovernmental mandates as defined in the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act (UMRA).

JCT and CBO have determined that the legislation would impose private-sector mandates as defined in UMRA. Based on information from JCT, CBO estimates the aggregate cost of the mandates would exceed the annual threshold established in UMRA for private-sector mandates ($156 million in 2017, adjusted annually for inflation).

CBO and the staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) prepared an estimate of the direct spending and revenue effects of H.R. 1628, the American Health Care Act, as posted on the website of the House Committee on Rules on March 22, 2017, incorporating manager’s amendments 4, 5, 24, and 25.

As a result of those amendments, this estimate shows smaller savings over the next 10 years than the estimate that CBO issued on March 13 for the reconciliation recommendations of the House Committee on Ways and Means and the House Committee on Energy and Commerce. The estimated effects on health insurance coverage and on premiums for health insurance are similar to those estimated for the committees’ recommendations.

Effects on the Federal Budget

CBO and JCT estimate that enacting H.R. 1628, with the proposed amendments, would reduce federal deficits by $150 billion over the 2017-2026 period; that reduction is the net result of a $1,150 billion reduction in direct spending, partly offset by a reduction of $999 billion in revenues. The provisions dealing with health insurance coverage would reduce deficits, on net, by $883 billion; the noncoverage provisions would increase deficits by $733 billion, mostly by reducing revenues.

Pay-as-you-go procedures apply because enacting the legislation would affect direct spending and revenues. CBO and JCT estimate that enacting the legislation would not increase net direct spending or on-budget deficits in any of the four consecutive 10-year periods beginning in 2027.

Effects on Health Insurance Coverage

CBO and JCT estimate that, in 2018, 14 million more people would be uninsured under the legislation than under current law. The increase in the number of uninsured people relative to the number under current law would reach 21 million in 2020 and 24 million in 2026. In 2026, an estimated 52 million people under age 65 would be uninsured, compared with 28 million who would lack insurance that year under current law.

Effects on Premiums

H.R. 1628, with the proposed amendments, would tend to increase average premiums in the nongroup market before 2020 and lower average premiums thereafter, relative to projections under current law. In 2018 and 2019, according to CBO and JCT’s estimates, average premiums for single policyholders in the nongroup market would be 15 percent to 20 percent higher under the legislation than under current law. By 2026, average premiums for single policyholders in the nongroup market would be roughly 10 percent lower than under current law.

Uncertainty Surrounding the Estimates

The ways in which federal agencies, states, insurers, employers, individuals, doctors, hospitals, and other affected parties would respond to the changes made by the legislation are all difficult to predict, so the estimates in this report are uncertain. But CBO and JCT have endeavored to develop estimates that are in the middle of the distribution of potential outcomes.

Comparison With the Previous Estimateate

On March, 13, 2017, CBO and JCT estimated that enacting the reconciliation recommendations of the House Committee on Ways and Means and the House Committee on Energy and Commerce (which were combined into H.R. 1628) would yield a net reduction in federal deficits of $337 billion over the 2017-2026 period. CBO estimates that enacting H.R. 1628, with the proposed amendments, would save $186 billion less over that period. That reduction in savings stems primarily from changes to H.R. 1628 that modify provisions affecting the Internal Revenue Code and the Medicaid program.

Over the 2017-2026 period, modifications to provisions affecting the Internal Revenue Code that are not directly related to the law’s insurance coverage provisions would reduce JCT’s estimate of revenues by $137 billion. Reducing the threshold for determining the medical care deduction on individuals’ income tax returns from 7.5 percent of income to 5.8 percent would reduce revenues by about $90 billion. Other changes include adjusting the effective dates and making other modifications to the provisions that repeal or delay many of the changes in the Affordable Care Act, which would reduce revenues by $48 billion.

A number of changes to the Medicaid program would reduce CBO’s estimate of savings by $41 billion over the 2017-2026 period. The reduction would result from revising the formula for calculating the per capita allotments in Medicaid to allow for faster growth of the per capita cost of aged, blind, and disabled enrollees. The effects of changing that formula would be offset somewhat by the effects of three other provisions that would increase savings: reducing the per capita allotment in Medicaid for the state of New York in proportion to any financing the state receives from county governments; providing states the option to make eligibility for Medicaid conditional on satisfying work requirements for enrollees who are not single parents of children under age 6 or who are not pregnant or disabled; and allowing states to receive a block grant for Medicaid coverage of children and some adults instead of funding based on a per capita cap.

Other smaller changes resulting from the manager’s amendments would reduce savings by an estimated $8 billion over the period.

Compared with the previous version of the legislation, H.R. 1628, with the proposed amendments, would have similar effects on health insurance coverage: Estimates differ by no more than half a million people in any category in any year over the next decade. (Some differences may appear larger because of rounding.) For example, the decline in Medicaid coverage after 2020 would be smaller than in the previous estimate, mainly because of states’ responses to the faster growth in the per capita allotments for aged, blind, and disabled enrollees—but other changes in Medicaid would offset some of those effects.

The legislation’s impact on health insurance premiums would be approximately the same as estimated for the previous version.